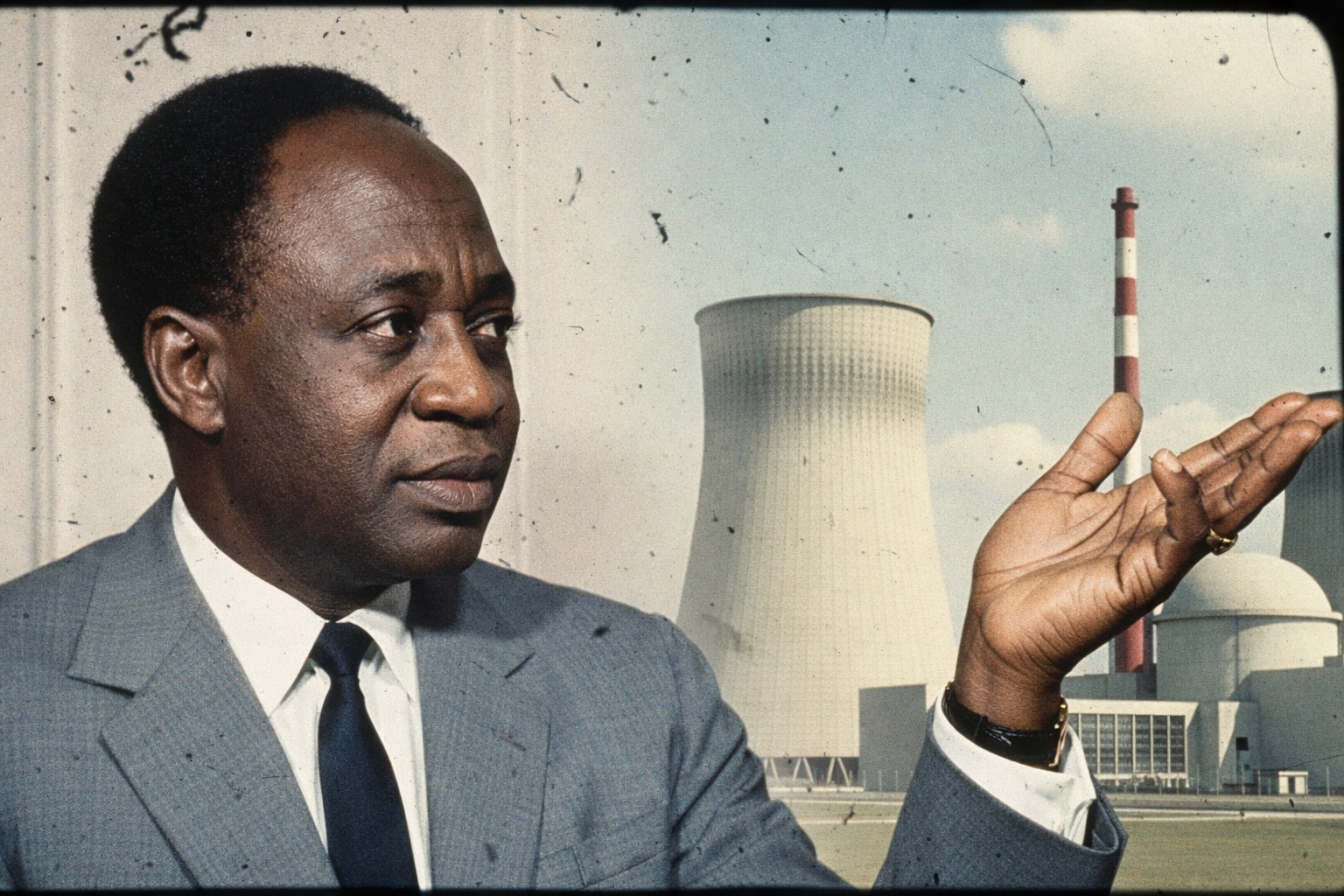

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah did not just dream of independence. He dreamed of dominance—scientific dominance. While most newly liberated African states were struggling to build roads, schools, and stable governments, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah was already thinking in atoms, reactors, and laboratories. He understood something many leaders of his era either ignored or feared: political freedom without technological power was simply another form of dependence.

In the early years of Ghana’s independence, nuclear science was not a fashionable topic for African presidents. It was a dangerous conversation, wrapped in Cold War paranoia and Western suspicion. Yet Dr. Kwame Nkrumah walked straight into it. He spoke openly about atomic energy, not as a weapon of destruction, but as a weapon of development. He pushed Ghana toward nuclear research at a time when the world’s nuclear gatekeepers believed Africa should remain a consumer of science, not a producer.

This was not a soft ambition. It was bold, calculated, and controversial. And when Ghana began serious cooperation with the Soviet Union—bringing Soviet expertise, equipment, and negotiations into the heart of Accra’s scientific planning—the world took notice. The West became uneasy. Local opposition became louder. The political temperature rose. Ghana’s nuclear journey stopped being a national development project and started becoming an international chess move.

Origins of His Nuclear Ambition (1952–1961)

Ghana’s engagement with nuclear science began not as a purely technological play, but as a political and economic strategy from the moment Dr. Kwame Nkrumah assumed leadership after independence in 1957. Radioisotope work in Ghana had started earlier (1952) with low-level scientific applications, but it was only under Nkrumah that the idea of a nuclear reactor for research and training was prioritized. (gaec.gov.gh)

By 1961, the Ghanaian government had formally launched the Ghana Nuclear Reactor Project (GNRP) and created the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission (GAEC) by an Act of Parliament (1963) to oversee everything related to peaceful nuclear activity. The goal was explicit: a research reactor would be used to train Ghanaian scientists and create the manpower needed for future nuclear power generation.

In his speeches, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah declared that atomic energy could be a cornerstone for national development—in agriculture, industry, and health—not for weaponization but for peaceful progress. Soviet personnel were repeatedly framed as cooperative partners in this plan.

Nkrumah and the Soviet Negotiations (1961–1964)

Official Soviet involvement began in the early 1960s under a series of bilateral arrangements. In October 1961, a contract was signed in Accra between Ghana and Soviet ministries (with Technopromexport acting as contractor) to support Ghana’s planned reactor. According to Soviet records, the USSR agreed to: design work, provide fuel elements, supply equipment, train Ghanaian specialists, send Soviet scientists to Ghana, and assist in building supporting infrastructure.

At that time, Robert Patrick Baffour (Vice-Chancellor, later KNUST) was chosen to represent Ghana on behalf of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. Baffour was sent to Moscow to negotiate with Soviet leaders, including Khrushchev, about nuclear cooperation. Nkrumah’s government openly linked this with the concept of scientific equity: that African nations, like others, could master high science if given access.

Several factors distinguished the Soviet approach in these negotiations:

- Supplies and training were to be provided with technical assistance and expertise, not as mere symbolic resources.

- Soviet specialists were to assist with siting, construction, supervision, and training of Ghanaian personnel.

- A research reactor (model IRT-2000) was selected which was smaller than power reactors but significant enough for advanced training and research. (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

By 1964, the reactor infrastructure was partially erected, cooling facilities were constructed, and many heavy components had been shipped to Kwabenya near Accra. According to Osseo-Asare and corroborated by contemporaneous records, the reactor was nearing 90% completion by early 1966.

Nkrumah repeatedly emphasized the peaceful purpose of the project and declared Ghana’s support for treaties such as the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, reinforcing that the program was not about weapons but societal development.

International Reactions and Cold War Tension

The nuclear program was not purely scientific but was enmeshed in Cold War geopolitics. Western governments—especially the United States, United Kingdom, and France—viewed Ghana’s Soviet engagement with deep suspicion. Cambridge University Press research notes that the choice of the Soviet Union for major nuclear assistance provoked anger in Western capitals, which saw such cooperation as expanding Soviet influence in Africa.

British intelligence and diplomatic cables from the period (examined by historians) show that Ghana’s nuclear initiative was closely monitored by Western powers, partly because Ghana was seen as strategically important and partly out of fear that nuclear technology might be misused or divert Ghana into the Soviet sphere of influence. Nkrumah’s critics within Ghanaed labeled him, sometimes pejoratively, as too close to the USSR, giving political ammunition to Western interests opposed to his pan-African socialist agenda.

The Coup of 1966 and Nuclear Disruption

The most pivotal controversy in this narrative is the February 24, 1966 coup d’état that removed Nkrumah from power. The coup abruptly halted the reactor project at its most critical moment. All Soviet cooperation was effectively frozen, the reactor was never fully commissioned, and many shipped components languished in storage for years.

Osseo-Asare clearly shows that the overthrow of Nkrumah was a turning point not just in politics but in scientific policy. The subsequent military government, composed largely of Western-aligned officers, mothballed the nuclear project, arguing that Ghana had greater priorities elsewhere and that hydroelectric power from Akosombo was sufficient for decades.

This suspension was deeply controversial. Nkrumah’s supporters argued that the abandonment of the reactor was a setback for Ghana’s scientific independence and that external forces played a role in removing a government committed to building technological parity. Critics argued that the project was impractical, costly, and unsuited to Ghana’s immediate needs. Both interpretations shaped Ghana’s political discourse for decades.

Later Nuclear Efforts (Post-1966 and Beyond)

Ghana’s nuclear aspirations did not die with Nkrumah, but they transformed. In the 1970s and 1980s, various governments attempted to revive the concept of research reactors or to procure smaller reactors from other countries (e.g., Germany), but political instability repeatedly derailed these efforts. (Nuclear Power GH)

Only in 1994 was a research reactor finally operational in Ghana: the GHARR-1, a Chinese-built miniature neutron source reactor, commissioned under IAEA cooperation. This reactor has been used primarily for research, training, and neutron activation analysis, not for power generation.

Controversial Interpretations (Unvarnished)

Political Pressure and the Coup Debate

It has been argued by some historians (and hinted at in Western diplomatic records) that the nuclear project and Nkrumah’s socialist affiliations made him a target for intense foreign political pressure. Western governments were openly irritated by Ghana’s Soviet engagements, and this generated mistrust that helped shape post-coup dismissals of his science policy. That argument is provocative and debated, but it appears amongst scholarshs as a real geopolitical factor.

Economic Practicality versus Visionary Ambitions

Critics have insisted that Nkrumah’s nuclear ambitions were out of sync with Ghana’s economic realities. Funding was strained, trained manpower was scarce, and hydroelectric projects were far cheaper to prioritize. Some internal critics at the time labeled the reactor endeavor as a luxury project that diverted attention from basic needs. While the scientific goal was clear, the implementation was arguably premature.

Soviet Motives While Soviet support was provided without the large profit motives associated with Western contractors, it was certainly not altruistic. The USSR saw nuclear cooperation as a way to expand influence in Africa during the Cold War—and this geopolitical rationale cannot be ignored when examining why the Soviets cooperated.

Kwame Nkrumah’s nuclear engagements with the Soviet Union were real, substantial, and consequential. These were not isolated technical discussions—they were embedded in Cold War politics, national strategy, and ideological confrontation. His policies were ambitious and frequently controversial, and the abrupt end of his government brought a significant shift away from his vision. The legacy is mixed: Ghana did eventually install a research reactor decades later, but the original Soviet project under Nkrumah was never completed, and the full potential his government envisioned for nuclear science was never realized. Together, the published sources paint a complex picture: one of political aspiration, international rivalry, scientific hope, and geopolitical consequence.