In an era where the global energy landscape stands at a critical crossroads, nuclear power is experiencing a remarkable renaissance. The International Energy Agency’s latest report, “The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy,” illuminates a compelling narrative of transformation and possibility. After decades of controversy and cautious progress, nuclear energy is witnessing an unprecedented resurgence, with over 40 countries now embracing supportive policies and increased investment in this well-established yet evolving technology.

As our world grapples with the dual challenges of energy security and climate change, this comprehensive analysis arrives at a pivotal moment. The report examines how nuclear power, with its proven track record of providing reliable, low-emission electricity for more than half a century, is positioning itself to meet the surging power demands of our increasingly digital world. From powering emerging data centers to supporting the global transition toward clean energy, nuclear technology stands ready to play a crucial role in our energy future.

The IEA‘s analysis delves deep into the intricate web of opportunities and challenges that lie ahead. It presents a detailed roadmap for how innovative technologies like small modular reactors, coupled with robust government support and novel financing models, could usher in a new golden age for nuclear energy. This thorough examination of nuclear power’s potential spans from current market dynamics to ambitious projections for 2050, offering valuable insights for policymakers, investors, and industry leaders alike.

What the Report Says

The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy is a new report by the International

Energy Agency that looks at the opportunities for nuclear energy to address

energy security and climate concerns – and at critical elements needed to pursue

these opportunities, including policies, innovation and financing. Nuclear energy

is a well-established technology that has provided electricity and heat to

consumers for well over 50 years but has faced a number of challenges in recent

years. However, nuclear energy is making a strong comeback, with rising

investment, new technology advances and supportive policies in over 40

countries. Electricity demand is projected to grow strongly over the next decades,

including from data centres, further underpinning the importance of having

sufficient new sources of stable low-emissions electricity.

The landscape of nuclear energy has undergone a remarkable transformation since 2020, when the International Energy Agency (IEA) first signaled an impending revival of the industry. This prediction came at a crucial time, as the nuclear sector was still recovering from the profound impact of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and the subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident—events that had cast a long shadow over the industry’s future. Now, four years later, that anticipated renaissance has materialized into a tangible reality, driven by an unprecedented convergence of factors: forward-thinking government policies that recognize nuclear’s role in energy security, groundbreaking technological innovations that address historical concerns, and a surge of private sector investment that signals renewed confidence in nuclear’s potential.

However, this resurgence, while promising, stands at a critical juncture. The path toward what many are calling a “new era” of nuclear energy remains complex, with significant hurdles still to be overcome. These challenges span technical, financial, and social dimensions, requiring careful navigation to fully realize nuclear power’s potential in our evolving energy landscape. Yet the momentum behind this transformation suggests that we are indeed witnessing the dawn of a new chapter in nuclear energy’s history.

In the global energy landscape, nuclear power stands as a cornerstone of clean electricity generation, surpassed only by hydropower in its contribution to low-emission energy sources. The industry’s trajectory has taken a decisive upward turn, with 2025 projected to mark a historic milestone in nuclear electricity production from the worlds ~420 Nuclear Reactors—a development that validates the International Energy Agency’s prescient 2021 forecast of nuclear’s resurgence.

This renaissance echoes the transformative period of the 1970s oil crises, when nations first began seriously considering nuclear power as a strategic energy solution. Today, that interest has reached similar heights, but with a crucial difference: more than 40 countries have now implemented concrete policies supporting nuclear expansion, reflecting a broader global consensus about its role in our energy future.

The industry’s revival is being further catalyzed by technological innovation, particularly in the realm of small modular reactors (SMRs). These revolutionary designs, expected to begin commercial operations around 2030, represent a fundamental shift in how nuclear power can be deployed and scaled. Their development comes at a pivotal moment in our energy transition, as we enter what energy experts are calling the Age of Electricity.

This timing is particularly fortuitous given the unprecedented surge in global electricity demand. Over the next decade, the growth rate of electricity consumption is projected to outpace overall energy demand by a factor of six. This explosive growth is being driven by a diverse array of factors: the electrification of industrial processes, the increasing need for climate control systems, the rapid adoption of electric vehicles, and the exponential expansion of data centers that power our digital world.

Technological Shift

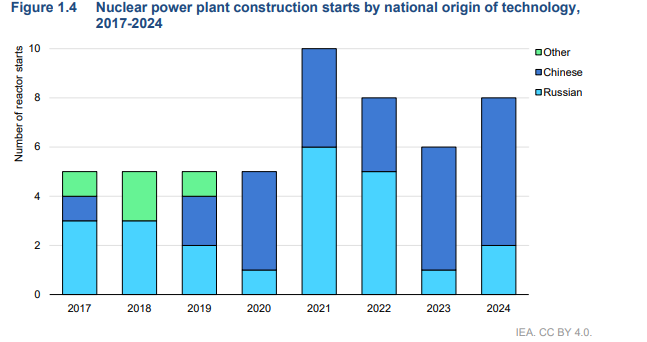

The global nuclear energy landscape has undergone a significant transformation in recent years, with a marked shift in market leadership from advanced economies to emerging powers, particularly China and Russia. Despite advanced economies retaining approximately two-thirds of global nuclear capacity, the dynamics of new reactor construction tell a compelling story of changing industrial dominance.

The period from early 2017 through the end of 2024 has been particularly illustrative of this transition. During this timeframe, 52 new nuclear reactor projects commenced construction worldwide. The distribution of these projects reveals a striking concentration: 25 reactors utilized Chinese designs, while 23 employed Russian technology. In contrast, advanced economies initiated construction on merely four reactors—two in the United Kingdom implementing European designs, and two in Korea using domestically developed technology.

This pronounced consolidation of nuclear technology providers raises important strategic considerations. The concentration of expertise and construction capability in just two major providers—China and Russia—could potentially create vulnerabilities in the global nuclear energy sector. Such market dominance may impact technological diversity, competition, and ultimately, the industry’s ability to innovate and adapt to evolving energy needs.

By the end of 2024, 63 nuclear reactors with a total capacity of 71 GW were under construction globally. China leads with 29 reactors (33 GW), nearly half the global total, mostly of Chinese design, with some Russian. India, Russia, Türkiye, and Egypt each have about 5 GW under construction, primarily Russian designs. Bangladesh and Ukraine also use Russian technology, making Russia the top nuclear exporter, with 23 GW in six countries and 4 GW domestically. Reactors in Japan, France, Brazil, Korea, and the UK rely on domestic or advanced economy designs.

In advanced economies, nuclear energy’s share of electricity generation has declined due to aging plants and reactor shutdowns, falling from 24% in 2001 to 17% in 2023. In the EU, the share dropped from a 1997 peak of 34% to 23%. In the U.S., it remains steady at 20%, with minimal growth in output over 20 years. In Japan, nuclear energy fell from 25% in 2010 to zero after Fukushima but recovered to 10% by 2023 as reactors restarted.

Delays In Construction

Nuclear power plant construction times significantly impact costs, with delays often leading to overruns. Compared to fossil fuel or renewable plants, nuclear projects are larger, more complex, and subject to stricter regulations. Since 2000, global nuclear reactor construction has averaged seven years, occasionally exceeding a decade, particularly in advanced economies. By contrast, utility-scale wind and solar projects are typically completed in under four years, sometimes less than two, though high-voltage transmission lines can take over a decade.

Construction times vary by region. The U.S. and Europe face prolonged timelines, while China averages seven years, achieving some completions in five. Korea’s reactors historically took four to six years, but recent projects stretched to a decade.

Advanced economies have seen escalating delays and costs. The U.S. Vogtle Units 3 and 4, initially budgeted at $5,600/kW, now cost $14,700/kW, with construction extending to a decade due to workforce issues and contractor changes. European examples include Finland’s Olkiluoto 3, delayed from 2009 to 2022, with costs doubling to $7,200/kW, and the U.K.’s Hinkley Point C, whose budget rose from $8,700/kW to $16,000/kW, with completion pushed to 2029–2031. France’s Flamanville 3 saw a 12-year delay, with costs tripling to $11,000/kW. Factors include the adoption of the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) design and a lack of recent domestic reactor construction, which required rebuilding industrial bases and skills.

Some projects have managed moderate delays and limited cost overruns. Korea’s Saeul 1 and 2 experienced 30% cost increases and delays of two to five years, reaching $2,700/kW. The UAE’s Barakah plant faced similar challenges, with manageable delays and cost increases.

Recent Decisions by Countries

SMR

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) have emerged as a central focus of innovation in the nuclear industry, with designs ranging from 10 MW to 350 MW in capacity. This technological advancement has sparked widespread development across the globe, with various countries pursuing different approaches based on their specific needs and capabilities.

The development landscape reflects diverse regional priorities. The United States and United Kingdom are concentrating on larger SMR designs, while China, Japan, and Korea are focusing on medium-sized reactors. Canada has oriented its development toward providing power to remote areas, and India is developing SMRs specifically for industrial applications such as powering steel mills. Within the European Union, countries are pursuing a range of sizes depending on their policy frameworks, energy security needs, and agreements with developers. Romania and Bulgaria are exploring small to medium-sized reactors, while the Czech Republic and Poland are considering larger installations.

African nations are also entering the SMR landscape. Kenya has set ambitious goals, targeting the construction of its first 300 MW SMR by 2027 with commissioning planned for 2034. Ghana has made significant progress by signing a commercial agreement with the Regnum Technology Group for developing SMRs below 100 MW using NuScale Power’s technology.

Beyond electricity generation, SMRs are proving versatile in their applications. They can serve as efficient sources of heat for district heating and desalination. Finland exemplifies this trend with plans to build an SMR dedicated to district heating, developed by Steady Energy. Their LDR-50 reactor is specifically designed for urban district heating, aiming to reduce fossil fuel dependence. This technology has attracted international interest, with Sweden’s Kärnfull partnering with Steady Energy to deploy the system in their country. Similarly, China is exploring the NHR-200, a 200 MW reactor, for district heating and desalination applications.

The industry currently encompasses over 80 SMR designs in various stages of development, with several companies leading the charge toward commercialization. NuScale Power, based in the United States, has made significant strides with plans for a 462 MW six-module VOYGR-6 SMR in Romania, targeted for completion in 2029. They have also established partnerships across multiple countries through memoranda of understanding and cooperation agreements.

Other American companies are also making substantial progress. TerraPower is developing a 345 MW demonstration plant in Wyoming, while GE Hitachi Nuclear is constructing the first BWRX-300 SMR at Ontario Power Generation’s Darlington site in Canada. X-energy is advancing its 320 MW Xe-100 reactor technology in Texas, and Oklo is preparing to construct its first SMR at the Idaho National Laboratory by 2027.

In the United Kingdom, Rolls-Royce SMR is developing a 470 MW design and has secured preferred supplier status in several European countries. France’s NUWARD is working on a 200 MW to 400 MW multipurpose SMR project, while Italy’s Newcleo is pioneering lead-cooled fast reactor technology with plans for installations in both France and the United Kingdom.

Asian developments are equally noteworthy, with China’s CNNC constructing the ACP100 SMR in Hainan province, potentially becoming the world’s first commercial land-based small modular PWR when it begins operation in 2026. Korea’s KHNP is advancing its 170 MW i-SMR project, targeting standard design approval by 2028.

The progression of SMR technology represents a significant evolution in nuclear power generation, offering flexible, scalable solutions for various energy needs. From providing baseload power to enabling district heating and desalination, SMRs are positioning themselves as versatile tools in the global energy transition. Their development across different regions and applications suggests a promising future for this technology in addressing diverse energy challenges worldwide.

Nuclear Investment

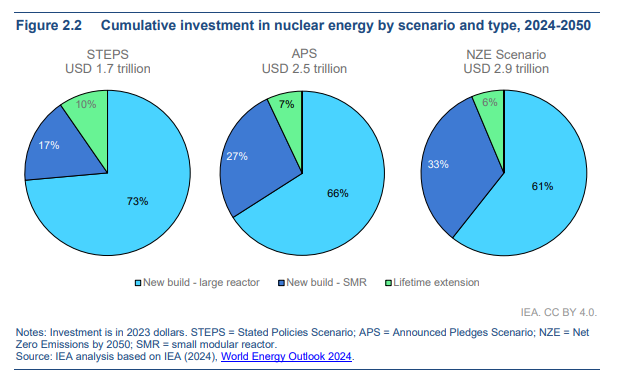

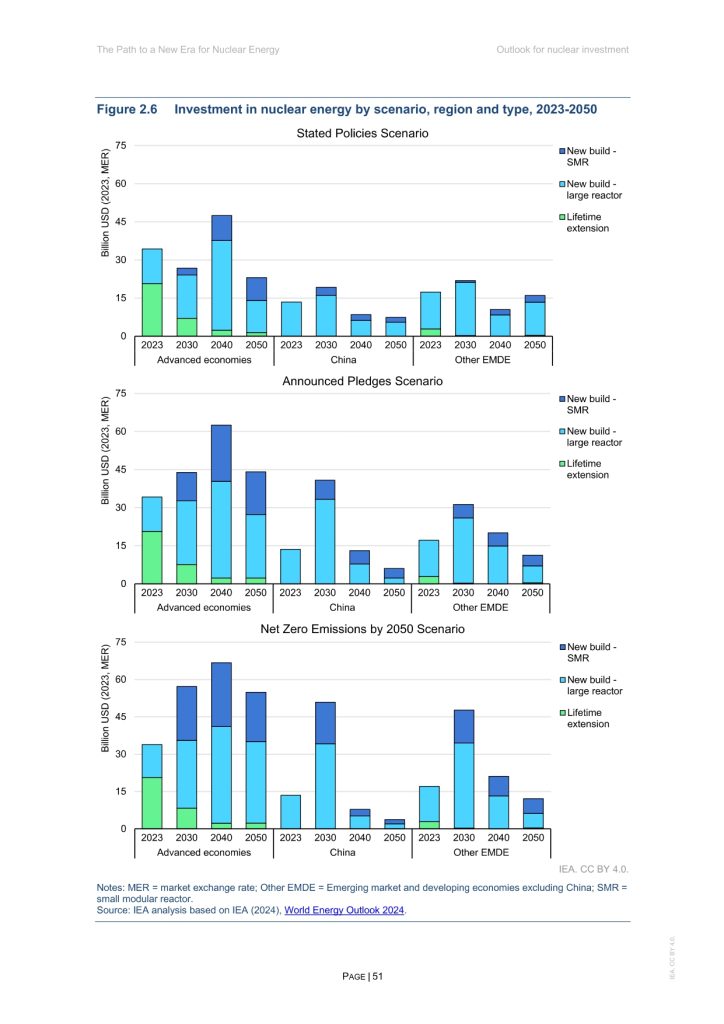

The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2024 projects significant changes in global nuclear energy investment across three distinct scenarios, each reflecting different combinations of government policies, climate ambitions, economic conditions, and technological developments.

Under the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), which reflects current policy settings, nuclear investment is expected to see modest growth from USD 65 billion in 2023 to approximately USD 70 billion by 2030. The majority of this investment—about 80%—will be directed toward constructing new large-scale reactors, while small modular reactors (SMRs) and lifetime extensions of existing facilities will each receive roughly 10% of the total investment. However, this scenario projects a decline in annual investment beyond 2030, particularly after 2040, with investments falling to USD 45 billion by 2050. This decline is primarily attributed to reduced reactor construction in China and decreasing costs for both large-scale reactors and SMRs.

The Announced Pledges Scenario (APS) presents a more ambitious outlook, with global nuclear investment nearly doubling to USD 120 billion by 2030, including USD 25 billion specifically allocated to SMRs. Similar to the STEPS scenario, investment levels eventually decline, reaching USD 60 billion by 2050. This decline is partly due to the achievement of power system decarbonization goals and continuing cost reductions in nuclear technology. Notably, SMRs gain increasing prominence in this scenario, accounting for more than one-third of total nuclear investment after 2040.

The Net Zero Emissions (NZE) Scenario projects the most aggressive near-term investment, reaching USD 155 billion by 2030, before moderating to USD 70 billion in 2050. This accelerated timeline reflects the urgent need to decarbonize power systems by 2040. However, all scenarios acknowledge that stronger-than-anticipated electricity demand growth could sustain higher investment levels in the longer term.

Looking at cumulative investments from 2024 to 2050, the projections range from USD 1.7 trillion in the STEPS to USD 2.5 trillion in the APS, and approximately USD 2.9 trillion in the NZE Scenario. While large-scale reactors dominate investment across all scenarios, SMRs are expected to gain significant market share from the 2030s onward. In the APS, for instance, SMRs are projected to attract USD 670 billion in cumulative investment by 2050, representing over 25% of total nuclear investments.

The deployment of SMRs varies significantly across scenarios. The APS projects the installation of more than 1,000 SMRs with a combined capacity of 120 GW by 2050, accounting for about 20% of all nuclear capacity additions. The NZE Scenario envisions even more rapid development, reaching almost 200 GW or over 1,500 reactors by 2050. In contrast, the STEPS projects more modest growth, reaching just 40 GW by 2050, reflecting insufficient policy support for rapid technology scaling.

The cost trajectory of SMR construction will play a crucial role in determining deployment rates. Initial projects are expected to have construction costs approximately double those of efficiently completed large-scale reactors, around USD 10,000 per kilowatt in advanced economies and under USD 6,000 per kilowatt in China and India. However, costs are projected to decline significantly as deployment increases and manufacturing processes become more efficient. In the APS, SMR costs are expected to achieve parity with large-scale reactors in the 2040s, falling below USD 5,000 per kilowatt. The NZE Scenario anticipates even faster cost reductions due to accelerated deployment, while the STEPS projects limited cost improvements due to reduced policy support for innovation and deployment.

Regional Outlook

Capacity in China is set to grow much faster than in the advanced economies, with

installed capacity overtaking that of the United States to become the largest in the

world by around 2030 in all three scenarios. By 2050, the nuclear fleet in China

expands from 57 GW in 2023 to 190 GW in the STEPS, 280 GW in the APS and

320 GW in the NZE Scenario. In other EMDE, the development of nuclear capacity

takes off after 2035, accounting for about one-quarter of the global nuclear fleet in

2050 in all three scenarios.

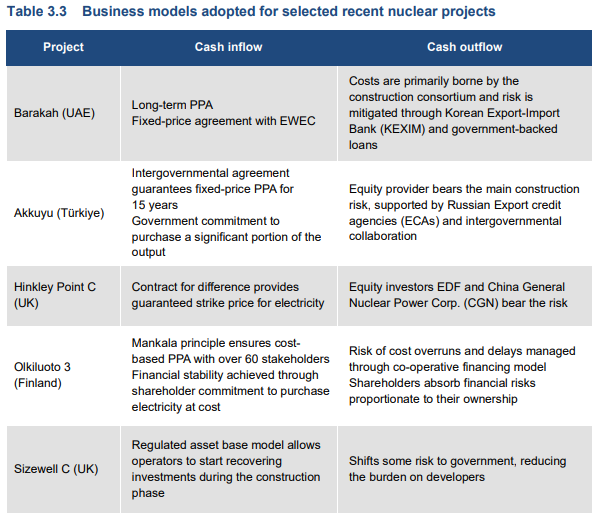

Financing Nuclear Projects

The enormous scale of a large-scale nuclear power plant, requiring initial

investment that can be in excess of USD 10 billion, means that most projects

struggle to get off the ground without some form of government involvement, either

in the form of direct ownership, lending, or other forms of financial support or

guarantees. This is particularly the case for first-of-a-kind projects, in new

countries, for new advanced large-scale reactor designs and for small modular

reactors (SMRs). But deploying more nuclear capacity in the coming decades will

happen only if the industry is able to unlock large amounts of commercial capital,

given the scale of the investment requirement and the constraints and competing

priorities for public budgets.

The financing of nuclear energy projects presents a complex landscape dominated by government involvement and characterized by specific challenges and emerging opportunities. State-owned utilities currently serve as the primary channel for nuclear energy investments, though private sector participation exists in markets like the United States and Finland. Even in these cases of private leadership, government support remains crucial through carefully structured regulatory frameworks and tariff systems.

The challenges in financing nuclear projects stem from several intrinsic characteristics of nuclear development. These projects require substantial capital investment, face extended construction timelines, and involve significant technical complexity. The risk profile is further complicated by the industry’s history of cost overruns and delays in recent projects, factors that often deter potential investors.

Government involvement has proven essential in bridging the gap between nuclear projects and commercial financing. By ensuring predictable cash flows and assuming construction risks, governments help nuclear projects achieve quasi-sovereign risk profiles, thereby reducing the cost of capital. This government backing is particularly crucial for securing debt financing, as financial institutions base their lending decisions on the reliability of future cash flow projections. In markets where electricity prices show significant volatility, various de-risking instruments become essential, including long-term power purchase agreements, contracts for difference, and regulated asset base models.

The capital structure of nuclear investments varies significantly depending on the project type. New large reactor construction projects, with their inherent risks during the construction phase, typically face greater challenges in securing bank financing, particularly in the early stages. In contrast, lifetime extension projects prove more attractive to financiers as they involve operational assets with established performance records.

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are emerging as a potentially transformative force in nuclear financing. Their reduced scale makes them more appealing to commercial investors, potentially broadening private sector participation in nuclear energy development. SMRs offer a significant advantage in terms of investment recovery, with projected payback periods potentially half the length of conventional nuclear projects’ typical 20- to 30-year timeframes, primarily due to shorter pre-project and construction periods.

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) could play a valuable role in nuclear financing, though their direct financial contribution may be limited. While the investment requirements for a single nuclear project often exceed the combined annual energy lending capacity of the eight largest MDBs, these institutions can contribute significantly by supporting the development of market designs and regulatory frameworks that facilitate nuclear project financing.

The emergence of green financial instruments represents a promising development for nuclear energy financing. Green bonds, in particular, have already channeled over USD 5 billion into nuclear projects, primarily supporting lifetime extensions and refinancing projects transitioning into their operational phase. This trend suggests growing potential for diversifying nuclear energy funding sources through sustainable finance mechanisms.

This evolving landscape of nuclear finance reflects both the persistent challenges and emerging opportunities in funding nuclear energy development. As the industry continues to innovate with new technologies like SMRs and adapt to changing financial markets through green instruments, the traditional government-centric financing model may gradually expand to encompass a broader range of funding sources and structures.