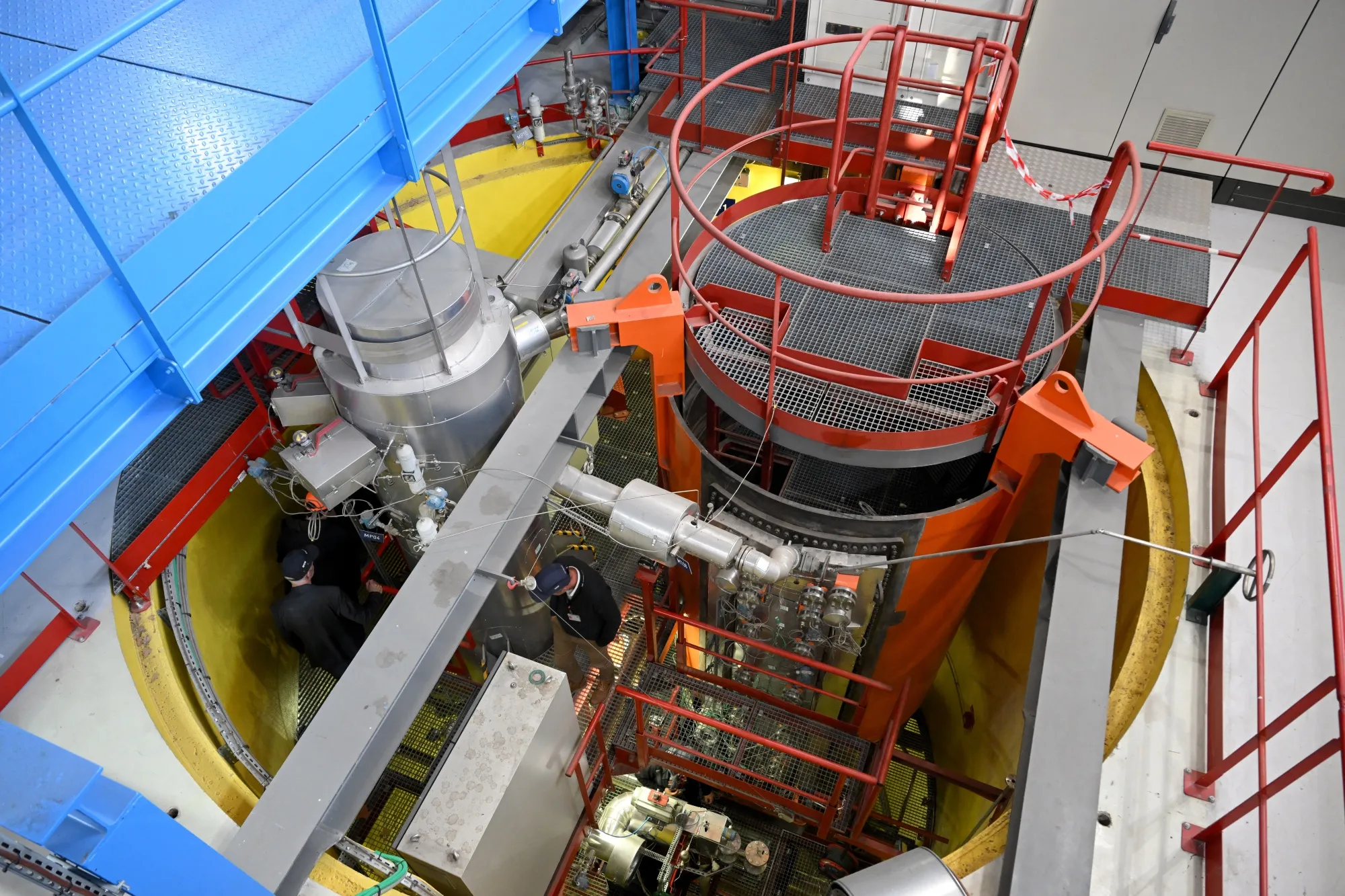

Small Modular Reactor (SMR)

The lights might finally stay on in Ghana—and the solution could be smaller than you think.

When over 170 people packed into Takoradi Technical University recently for a workshop on nuclear energy, it wasn’t just another academic gathering. It was a turning point in how Ghana thinks about solving its persistent electricity challenges. The topic? Small Modular Reactors, or SMRs—compact nuclear power plants that experts believe could transform the country’s unreliable power supply into something we can actually depend on.

Why This Matters Now

If you’ve lived in Ghana, you know the frustration. The power cuts, the “dumsor” that cripples businesses and makes everyday life unpredictable. We’ve tried various solutions, but nothing has fully solved the problem. That’s what makes this conversation about SMRs so important—it’s not about choosing between solar panels or gas turbines anymore. It’s about finding a reliable backbone for our entire energy system.

Professor Ebenezer Boakye, TTU’s Pro-Vice-Chancellor, didn’t mince words at the workshop. “To secure our development, we must build a resilient national energy system,” he told the crowd. “This means combining our vast renewable energy potential with a dependable, always-available power source. Nuclear energy provides that reliability.”

What Exactly Are Small Modular Reactors?

Think of SMRs as the smartphone version of nuclear power—smaller, smarter, and more flexible than the massive nuclear plants you might picture. Unlike traditional reactors that take decades to build and require huge investments, these modern designs can be manufactured in factories and assembled on-site. They’re called “modular” because you can add more units as your power needs grow.

The key advantage? They never stop producing electricity. While solar panels go dark at night and wind turbines sit idle when the air is calm, SMRs keep running 24/7, rain or shine. That’s exactly what Ghana’s industries and homes need—power they can count on.

The Research That’s Changing Minds

Mark Amoah Nyasapoh, the energy economist leading this research, presented findings that got everyone talking. Using sophisticated computer models—tools with names like HOMER and MESSAGE that are used by energy planners worldwide—his team showed what could happen if Ghana combines SMRs with our existing renewable energy sources.

The results were striking: stable electricity prices, dramatically lower carbon emissions, and reliable power for everything from heavy industries to remote villages that have never had consistent electricity. “This isn’t theoretical—it’s a practical pathway to breaking Ghana’s recurring power crisis,” Nyasapoh explained to the audience.

For him, this is personal. As someone working at Ghana’s Atomic Energy Commission and pursuing a PhD at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, he’s dedicated to finding real solutions. “By guaranteeing stable and continuous power, we can sustain major infrastructure projects, fuel industrial expansion, and enable businesses to operate reliably around the clock,” he said. “This has the potential to stimulate economic growth, generate employment, and attract investment.”

Addressing the Elephant in the Room: Safety

Let’s be honest—when people hear “nuclear power,” many think of Chernobyl or Fukushima. That fear is understandable, which is why Professor Hossam A. Gabber from Ontario Tech University in Canada tackled it head-on during his keynote address.

“Modern SMR designs prioritize inherent safety and are engineered with multiple, independent protection layers,” he explained, referring to what engineers call “defense-in-depth.” In plain English, that means these reactors are built with backup systems for their backup systems. They’re designed to shut down safely even if everything goes wrong.

The technology exists to deploy nuclear power that’s not only clean and cost-competitive but fundamentally safe for communities. These aren’t your grandfather’s nuclear reactors—they represent decades of learning from past mistakes and engineering improvements.

From Talk to Action

What sets this workshop apart from countless others is the commitment to actually doing something. TTU’s Vice-Chancellor, Rev. Professor John Frank Eshun, didn’t just nod along—he committed the university to training the engineers, operators, and safety experts Ghana would need to make nuclear power a reality.

There’s already talk of establishing an SMR simulator and hybrid-energy data center at TTU, in partnership with Ghana’s Atomic Energy Commission and Ontario Tech University. This wouldn’t just be for show—it would be a practical training hub where Ghanaians learn to operate and maintain this technology.

Dr. Archibold Buah-Kwofie, who directs the Nuclear Power Institute at Ghana’s Atomic Energy Commission, put it simply: “Building local capacity is non-negotiable for Ghana’s energy transformation.”

What Happens Next?

Can Ghana really go nuclear? Should They? How long would it take? What would it cost?

These are the right questions to be asking. Ghana’s energy demand keeps growing while our supply remains unreliable. Industries can’t plan for the future when they don’t know if the lights will be on tomorrow. Families shouldn’t have to budget for generators and fuel just to keep food fresh or children studying after dark.

SMRs aren’t a magic bullet that will solve everything overnight. But they could be the missing piece in Ghana’s energy puzzle—the steady, reliable foundation that allows solar, wind, and hydro to shine without leaving them in the dark when nature doesn’t cooperate.

The workshop at TTU has done something important: it’s moved nuclear energy from the realm of “maybe someday” into the category of “let’s figure out how.” With U.S. State Department funding through the FIRST Programme and partnerships with international experts, Ghana is taking concrete steps rather than just talking.

Whether this leads to Ghana’s first SMR being built in five years or fifteen, the conversation has started. And for a country tired of power outages, unreliable electricity, and missed economic opportunities, that conversation couldn’t come at a better time.

The question isn’t whether Ghana needs reliable, clean, affordable energy. They clearly do. The question is whether they’re bold enough to embrace the technology that could finally deliver it.